Rehab & Training - Part 3 Recovery

The Story So Far

In this series of three articles we have considered whether “mainstream” training for strength and conditioning has lessons for neurorehabilitation. If you have read our previous articles you will know that we believe it has many lessons for us. We have so much left to learn though.

We know that the body/brain/nervous system can adapt to applied stress. Stress, depending on how it is applied can obviously help or harm us. Training is about controlling the nature and extent of that stress to produce the adaptions in the mind/body system that we desire.

When we train as athletes, we train to improve physical and mental performance and many of our clients of course train to recover the functions they lost due to a neurological condition. Recognising the fact of neuroplasticity has brought hope that many people can indeed recover lost function but this remains a non-trivial task.

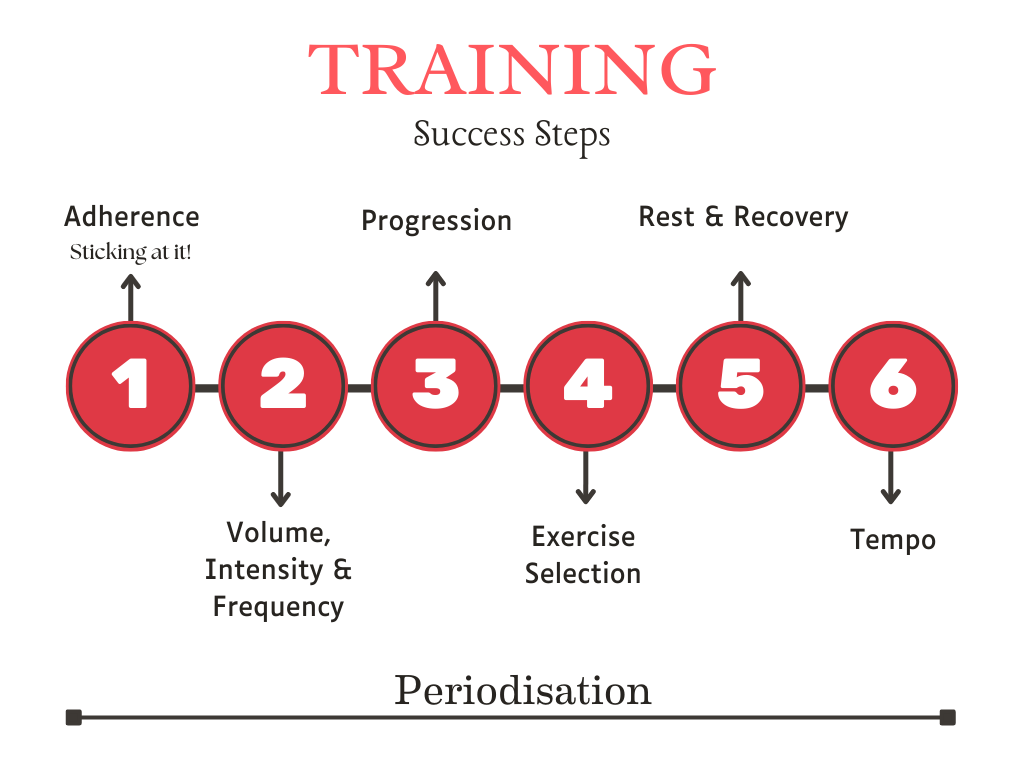

In article one in this series, we looked at the factors for training success - commencing with adherence. The art of starting to train and being able to “stick at it” is fundamental to progress.

Whether we are thinking of professional sport or neurorehabilitation following a stroke or spinal cord injury, if progress is to be made, adherence is fundamental.

To make progress you have to be able to commit to a pattern of regular training. For neurorehabilitation, this means having access to a training facility in an accessible location, with support from a knowledgeable person and at an affordable price. This is a big barrier for many before training even commences.

Adherence implies that you cant just train intensively for a short period and expect to maintain the gains made for too long. We all know this from personal experience. If you have ever exercised and enjoyed a particular level of fitness, you will know that such fitness declines pretty quickly if you have had a layoff for some reason. The more strength and fitness you have in the bank the more you can “afford” a layoff without affecting quality of life. For all of us humans, the fact is that exercise is medicine. If we do not, or cannot, move and generate power with our bodies we are in decline.

As a society we have a massive problem of elderly people who lose strength in their later years, then become susceptible to a range of health conditions and become dependent on others for their care. This age-related decline in strength is not inevitable - but that’s another story.

Programme Design is Challenging

If you glance at the elements of a training programme as in the figure above, you see there are always many decisions to be made in designing a training programme. Adherence might be the start but turning up to training isnt enough. You have to do the right things.

In article 2 of the series, we considered the training dose - the combination of volume, intensity and frequency of exercise. We also have to consider how to apply and adjust the training dose along with the specific method of exercise and the period at which this is repeated. The training process is a motor learning one. In neurorehab we hear the basic training recipe - intensely goal-directed, task-specific and challenging practice.

For athletes, choosing training parameters can be something of a “black art” but at least we know some of the general levers of influence that we can tweek to build strength and power, cardiovascular fitness, mobility and so on. In neurorehabilitation, we generally cant be quite so confident about how to shape a training programme for functional recovery. We as always, recognise that individuals vary in their response to a programme and our starting point must always recognise and deal with contraindications.

As the researchers say - there is always need for further research. There is also reason to treat this as a multidisciplinary issue. Bringing together strength and conditioning professionals, sports scientists, physiotherapists and occupational therapists would be valuable.

Rest and Recovery

At last we get to the topic of rest and recovery. If you are an athlete, training needs to be taken often enough and hard enough to produce the adaptive stress necessary to become more skilled, faster, stronger or bigger. I know people who train every day, others who train several times a day and others who train two or three times per week. They all will have different training goals and differing abilities to respond to training and then recover.

To make progress toward a training goal it is necessary to push yourself. To be the best in the world, athletes really need to push themselves. This fact has to be balanced with the need for rest and recovery. As a powerlifting competitor in my youth, I was lucky enough to have a coach who pointed out that I wasn’t getting stronger while I was in the gym. I was getting stronger due to the adaptations that were taking place during rest and recovery.

In elite sport, rest and recovery is a hot topic but still elusive to pin down. What exactly is the ideal amount of rest and recovery? How do you know if it’s correct for an individual? How essential is this topic to neurorehab?

It is known that if you train for two hours per day, what you do with the remaining twenty-two hours really counts. Patterns of sleep, nutritional status and stress due to life’s general distractions can be barriers to recovery. The concept of periodisation is shown spanning the success steps of training above because it is fundamental to balancing the dose of training with rest and recovery. Let’s explore what helps or hinders recovery

How Successful Athletes Respond to Exercise

When elite athletes are training intensively in a phase of their training it is normal for them to feel tired and see performance drop. When they rest and recover most effectively, adaptation to the stress of training is positive and performance is gained. However, we could reasonably ask, is it possible to over-recover? If we have ever exercised intensively you will intuitively know that it is indeed possible to over-recover. Whilst it might seem sensible to have a lengthy recovery period, if this is too long then it blunts the adaptation process. Positive adaptations to muscle, bone and the nervous system occur following the stress of training but if there is too much rest then this adaptation is blunted and progress does not occur. Sports science is trying to solve this delicate balance.

In the diagram above I have tried to show the elements of training alongside the elements of recovery.

Nutrition, Sleep and Unhelpful Stress

First of all we need to stop thinking of recovery as just relevant to the period after training. This is because recovery is going to be the method that also precedes, and sets you up for, the next training session. Many athletes think of recovery as a set of tactics to be used such as ice baths, compression garments, massage etc. Whilst these might help, they are not fundamental to recovery. I have put these in the figure above as “Treatments” - useful but not fundamental to recovery.

Nutrition, sleep and avoiding unhelpful stress ARE fundamental to recovery

If the athlete is not taking care of nutrition, is not sleeping well and is stressed out in their private life, no amount of massage or ice baths will make much difference.

I feel that success in neurorehabilitation is also likely to be influenced by these factors - attention to nutrition - sleep hygene and avoidance of unhelpful stress.

These factors are also of course very important in terms of overall health. After all, whether you are an athlete or recovering from a neurological condition, health is fundamental. Next in order of importance is the Training Plan. It’s pretty obviously that the nature of the training plan will be important in shaping the quality of rest and recovery.

Monitoring

Monitoring is on the list of recovery influences and there is good reason for this. We are dealing with a complex issue and who can resist having more data. Technology today allows us to quantify human performance - force and power generation and speed - and what is happening inside the body. I can slip a sensor on my finger that can accurately determine my heart rate and heart rate variability, my O2 saturation levels and respiration rate. I can easily monitor instaneous blood glucose levels and much more. Blood tests can reveal the secrets of my metabolism and nutritional status. Being able to look at my autonomic nervous system balance can give useful insights into levels of stress and recovery status. Measurement and monitoring will be important but not dominate matters.

Conclusion

As a company we are passionate about rehabilitation and improving the lives of those who need it. In this series of articles we have suggested that training for neurorehabilitation has many unknown elements at the moment.

It is a motor-learning process that has elements of skill and strength development. It is often described in terms of the need for training to be intensely goal-directed, task-specific and challenging practice. This leaves many questions about the specific training plan unclear. Relatively few studies have yest considered how to vary training parameters for best effect. Even fewer have looked at the need for rest and recovery.

In these articles, we have looked at strength and conditioning training to see if this more familiar territory might give us a structure with which we might approach training for neurorehabilitation. In this final article, we have introduced the important of rest and recovery. The best results from training are achieved when there is an optimal balance between the training dose and rest and recovery. This has many unknowns but we can rely on the vital importance of sleep hygene, nutritional status and maintaining. as far as possible, low levels of negative stress.