How to Prevent Heel Pressure Ulcers: First Understand What Causes Them?

Do you know how to prevent pressure sores on heels? First understand that heel pressure ulcers can be a challenging problem to manage and prevention is best! With prolonged pressure on the skin, inadequate nutrition, and lack of movement being significant factors that lead to their development, it is a condition that everyone should take seriously.

There are many well-known risk factors for developing heel pressure ulcers, making it all the more crucial to avoid them in the first place. The good news is that with proper rehabilitation and prevention techniques, these heel pressure ulcers can be avoided. Whether it's using the correct equipment, moving around frequently, or changing positions regularly, there are several approaches to lower the chances of developing heel pressure ulcers. Despite the many challenges that lie ahead, it is essential to take action to better combat this issue.

What are Heel Pressure Ulcers

heel pressure ulcer

A pressure ulcer, also known in the past as a pressure sore or bedsore, is an area of skin and often deeper tissue damage, that occurs, in part, as a result of prolonged pressure on the skin. It sounds straightforward, but there is a bit more to it as we shall see.

Here is a Definition from Clinical Practice Guidelines

"Any skin lesion, usually over a bony prominence, caused by unrelieved pressure resulting in damage of the underlying tissue"

Pressure ulcers most commonly develop on areas of the body with a relatively thin layer of tissue. These areas are often vulnerable when subject to constant pressure so people who are immobile are particularly at risk. Areas such as the heels, ankles, hips, and tailbone are particularly vulnerable. They can also occur on the elbows, shoulders, and back of the head. We will focus on the heel area but the same general principles apply.

Who is Most At Risk?

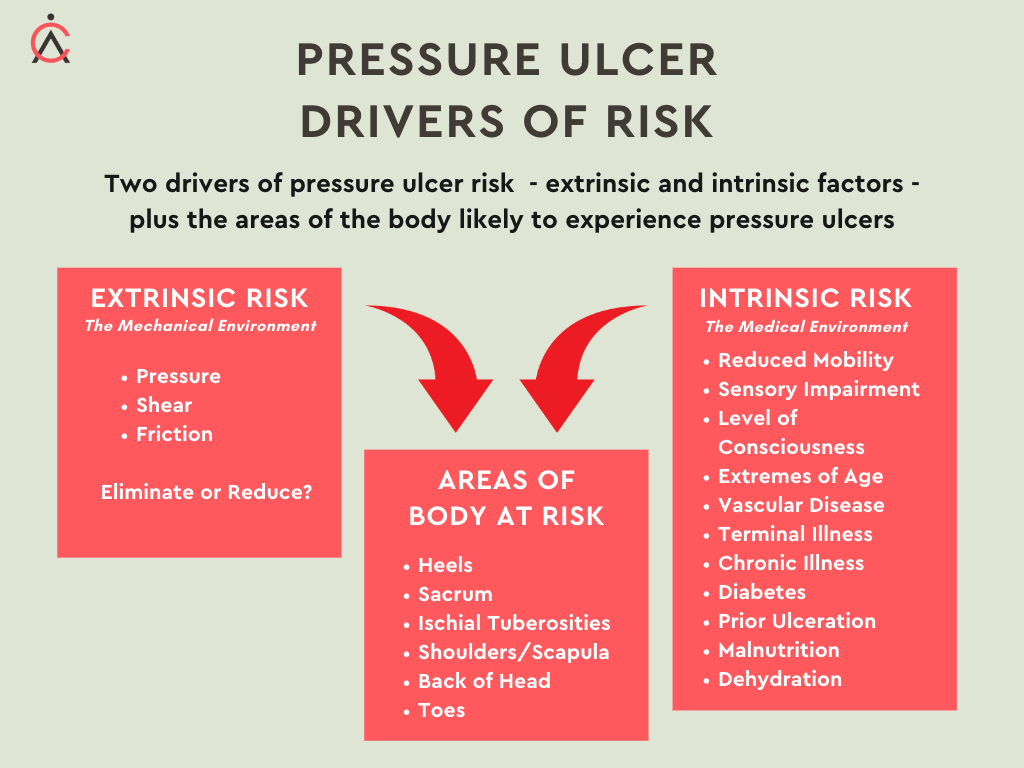

We could describe the risk of developing a pressure ulcer in terms of both medical and biomechanical factors. There are many facets to this.

The medical risk factors include the following shown on the image as instrinsic risk. Another way of thinking about this is as follows - High blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking are all common medical risk factors that can increase the likelihood of developing cardiovascular problems. Having a family history of heart disease can also be a sign that you may be at greater risk. Additionally, leading an inactive lifestyle or being overweight increases your risk even further. It is important to regularly monitor these health conditions and make sure you are taking the necessary steps to maintain a healthy weight and lifestyle. Taking action now can help you reduce your risk in the future.

It is also important to understand any non-medical risks that may be present, such as environmental or lifestyle factors. Stress, poor diet, excessive alcohol consumption, and lack of exercise all put you at greater risk for developing cardiovascular problems

Pressure Ulcer Drivers of Risk

This list points to the complexity of the situation and the importance of recognising at the earliest stage those individuals likely to be at more risk. The intrinsic risk relates to the persons medical and general condition and of course it is imperative to control as many of these influences as possible.

There are of course limitations - for example, we can’t cure diabetes but we can ensure that blood sugars are well regulated and check for peripheral neuropathy.

The so-called mechanical factors - Pressure, Friction and Shear - are in essence just as complex as the medical factors but we may feel more able to manage these influences.

Potential Causes of Heel Pressure Ulcers

The great French physician, Jean-Martin Charcot studied the decubitus, or pressure ulcer in the 19th Century. He did not believe that pressure or local irritation were causative factors for the decubitus but he rather attributed this to the “neurotrophic theory,” which held that damage to the central nervous system led directly to ulceration.

Charcot observed that many patients who developed eschar of the sacrum and buttocks died soon afterwards, and he referred to this lesion as the decubitus ominosus, implying that its occurrence suggested death was imminent.

His description of the evolving decubitus is extraordinarily detailed and accurate and includes complications generally never seen today, such as gangrenous metastases to the lung and invasion of the spinal cord.

A pressure ulcer can therefore be viewed primarily as a biomechanical issue, although the cascade of clinical events we highlighted above often involve many confounding intrinsic and extrinsic factors, such as the general health condition, nutritional status and even the personal hygiene of the subject involved. Decades of research have clarified some mechanisms leading to pressure ulcers, although considerable controversies still remain. In general terms, the methods for clinical prevention and intervention for pressure ulcers have seen few breakthroughs over the years, despite the enormous magnitude of the clinical problem and the recent advances in medical science and practice

The Role of Pressure, Shear and Friction in Prevention

As a Bioengineering student many years ago we strove to measure pressure at the tissue interface of areas at risk and use mathematical models to consider deep tissue stress and strain. It is important to understand that the effects which can be so destructive are not just taking place at the tissue surface. When surface pressure is applied, various deep tissues, blood vessels and related cells are affected as tissues deform under the load. These deep effects are very challenging to measure or model.

We still today have imperfect models of the behaviour of these tissues under load.

The tissues of the body vary in their mechanical properties from one part of the body to another and from one person to another; engineers would describe tissue as anisotropic, inhomogeneous, and nonlinearly viscoelastic. If life wasn’t difficult enough, we know that these mechanical properties can change with ageing and pathological conditions. If an area of tissue has been ulcerated once, then we know it will always remain vulnerable because of the nature of the tissue that formed during healing.

Visualising the pressure and shear force in the heel area at risk

Ultimately this seems like a job for many lifetimes. In the short term we need to do the best we can.

In practice, we used “rules of thumb” to think about how these mechanical factors will relate to pressure ulcer risk.

Fundamentally we believed that high pressures could only be tolerated for a short period of time and lower pressures for a longer period of time.

Theoretically then we could envisage combinations of pressure and time that would be “safe” and combinations that would result in an ulcer. The problem has always been we don’t know where the boundary between safe and unsafe will be for an individual.

The only safe level of pressure on an area at risk is ZERO.

When we consider friction and shear, we know that these effects can be more destructive than pressure applied to the surface of the tissues. Friction between tissue and a support surface is again always important when tissues deform under load from that support surface. These surface loads have consequences for deep tissues.

Different Types of Heel Protectors

There are many types of heel protectors on the market and the the temptation is always to look for something which serves the purpose at least cost. Care needs to be taken however to define “purpose” carefully.

Part of the PRAFO range of ankle foot orthoses

We should also consider the need for continuity of care. In other words, be conscious of the next stage in the treatment plan.

When the PRAFO range was designed the aim was to provide more than a heel ulcer protection device. All of the PRAFO models provide zero pressure at the vulnerable heel area, but also can allow safe mobilisation, prevent the development of contractures and support many aspects of the patient’s journey to recovery. The range is available with various liner interfaces and in paediatric and infant sizes.

Conclusion:

In order to prevent heel pressure ulcers, it is important to understand what causes them and what is needed to keep patients safe and protected. This post has outlined the challenge we have to reduce the risk of pressure ulcers that arise due to both medical and biomechanical influences. We offer the PRAFO range of ankle foot orthoses that offer zero pressure at the heel. The same products can be used to allow or maintain mobility, prevent contractures and manage shear and friction.

Readers are encouraged to contact an orthotist or other competent professional such as a tissue viability specialist to discuss best practices for the care of heel pressure ulcers, as well as provide tips for the patient’s own self-care.