How are spinal cord injuries classified?

An introduction to our blog article on the subject of how spinal cord injuries classified?

A spinal cord injury can be a life-changing event that no one is ever prepared for. Medical science has learned a great deal about how to treat the short-term consequences of a spinal cord injury. In the longer term, the imperative is to recover whatever function can be recovered through focusing on rehabilitation. Assistive technology can help to compensate for function that cannot be recovered. By preventing complications and striving for health, individuals can expect to enjoy good quality and length of life.

The mindset, attitudes and beliefs of the injured person and those around them will have a great impact on their potential for recovery, but there are limits to how far ‘belief’ will take them. Just believing that something is possible is not enough to make it so. We live in an age when technology, therapy and medical science can help individuals recover more function or at least remain healthier than would have seemed impossible just a few years ago. Whilst there is no cure yet for spinal cord injury, this no longer seems an impossible dream.

Every spinal cord-injured person faces a different challenge as they essentially have injuries with somewhat different characteristics. To deal with this, medical science has sought to find a way to classify spinal cord injuries in a way that helps to guide treatment, and to some extent, define the expectations for recovery. This article examines how spinal cord injuries are classified.

The spine, spinal cord and function

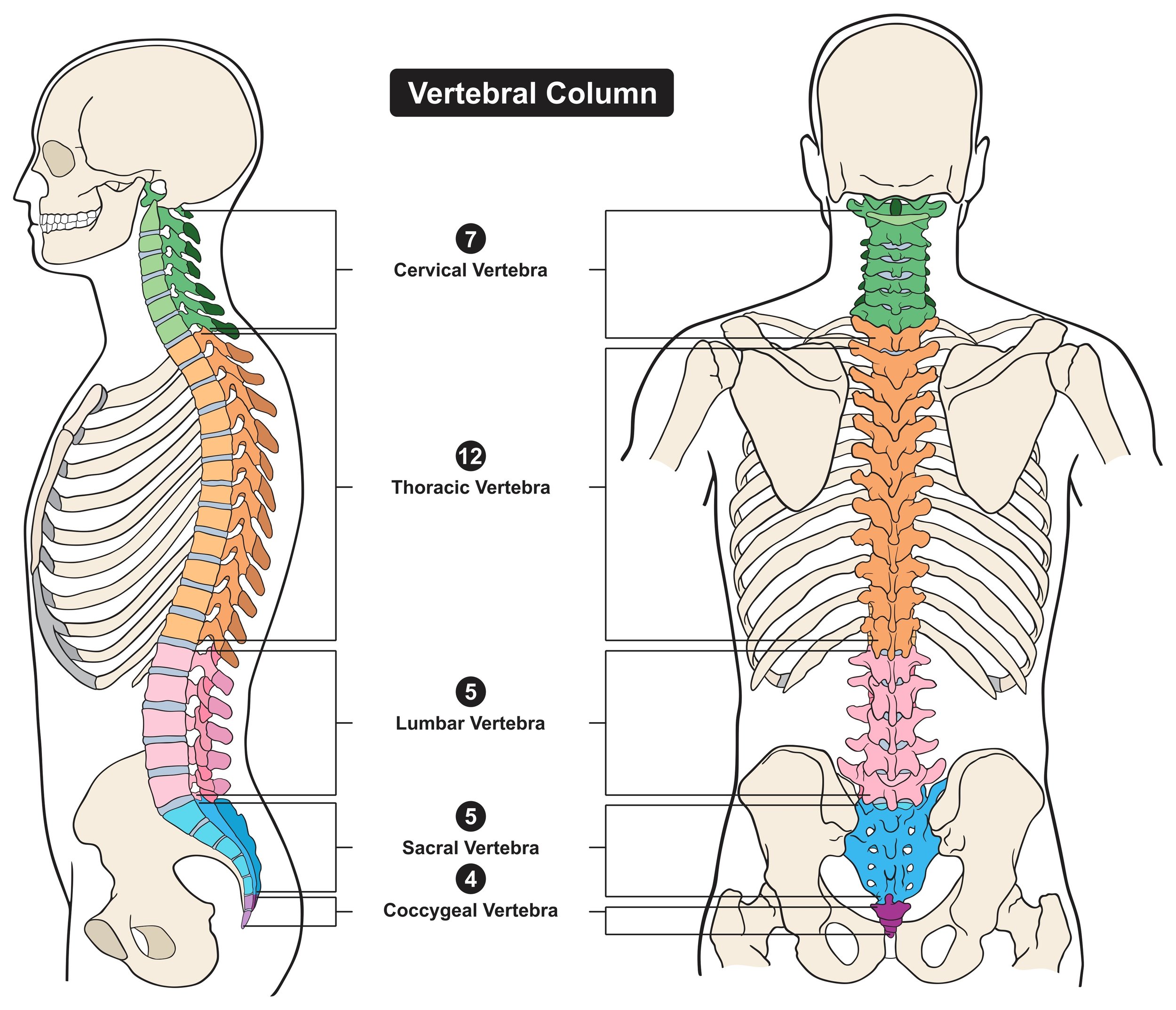

The spinal cord is situated within the protective bony spine, which consists of a series of vertebral segments that are described as cervical (neck area), thoracic (mid-back), lumbar (low back) and sacral (low back at the pelvis). The spinal cord itself also has so-called ‘neurological’ segmental levels which are defined by the spinal roots that enter and exit the spinal column between each of the vertebral segments. The spinal cord segmental levels do not necessarily correspond to the bony segments.

When people are injured, they are often told that they have damage to particular bony vertebrae and the cord itself at a given level, along with a further qualifier suggesting the severity of the injury, ie ‘complete’ or ‘incomplete’. The original grading system used to classify injuries was the Frankel classification (Frankel et al 1969). This was improved over time and the grading system commonly used now is the American Spinal Injury Association system (ASIA, 1982).

Let's look in more depth into the level and location of a spinal cord injury and why this matters.

It’s important to understand that the physical consequences of a spinal cord injury vary with its location and severity. This dictates which parts of the body and organ systems are affected and influences the expectations (not least in the minds of the medical professionals) for treatment and the potential for recovery.

When your nervous system is working properly, it carries messages to and from your brain and body parts. The nervous system is complex, but in essence, these messages control at least three important functions:

The motor functions which determine your ability to consciously control the contraction of your muscles, and hence the movement of your limbs to carry out everyday tasks.

The sensory functions that reflect the sensation of touch: controlling your ability to ‘feel’ things and be aware of the position of your limbs in space even with your eyes closed.

The autonomic functions, which refer to actions that your brain controls without you having to think about them. Your heart beating and your lungs taking a breath are examples. Interestingly, just because functions are autonomic, it does not mean that you cannot consciously influence them. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) has a powerful effect on many organ systems and is central to how we all behave under stress.

In basic terms, the closer the damage to the spinal cord is to the head and neck, the more parts of the body are affected and potentially the greater the degree of disability. This is because the nerves at a vertebra represent a part of the communication path between the brain and the various body systems below that level.

When the spinal cord is damaged, messages cannot ‘jump over’ the damaged area. In other words, the messages sent from the brain cannot make it to body parts below the damaged area, and vice versa. Thus, the body at and below the level of injury is affected, but our bodies are resilient, and the nervous system will attempt to ‘rewire’ itself and work around the problem. Current research and clinical practice encourage this process.

The ASIA Classification

The ASIA system is now recognised internationally as the way to classify spinal cord injuries, and it can also classify improvements over time. As you might expect, it is used to group and compare patients and predict functional outcomes for rehabilitation.

The definition of spinal cord injury levels and the classification of the injury can seem confusing if you haven’t met them before. A basic description of injury at various levels is:

Cervical. The neck area contains seven cervical vertebrae (C1 to C7) and eight cervical nerves (C1 to C8). Cervical injuries usually cause loss of function in the chest, arms and legs. They can also affect breathing and bowel and bladder control. These effects are in addition to loss of function in the thoracic, lumbar and sacral regions.

Thoracic. At the central chest area there are twelve thoracic vertebrae (T1 to T12) and twelve thoracic nerves (T1 to T12). Thoracic spinal cord injuries usually affect the chest and the legs. Injuries to the upper thoracic area can affect breathing. Thoracic injuries can also affect bowel and bladder control.

Lumbar. The lumbar area (between the chest and the pelvis) contains five vertebrae (L1 to L5) and five nerves. Lumbar injuries usually affect the hips and legs, and can also affect bowel and bladder control.

Sacral. The sacral area (from the pelvis to the end of the spine) contains five sacral vertebrae (S1 to S5) and five sacral nerves (S1 to S5). Sacral spinal cord injuries usually affect the hips and legs. Injuries to the upper sacral area can also affect bowel and bladder control. For example, in an injury between C1 and C8, messages to and from the brain are stopped in the neck area. This usually results in at least some paralysis of the chest, arms and legs (tetraplegia, also known as quadriplegia). In an L3 injury, messages are stopped at the lower back. This results in at least some paralysis of the legs and hips, which is referred to as paraplegia.

Injuries are also described as complete or incomplete. The ASIA system further classifies injuries into four subsections:

A: Complete. No feeling or movement of the areas of your body that are controlled by your lowest sacral nerves. This means you do not have sensation around the anus or control of the muscle that closes the anus, so people with complete spinal cord injuries do not have control of bowel and bladder function.

B: Incomplete. There is feeling, but no movement below the level of injury, including sacral segments that control bowel and bladder function.

C: Incomplete. There is both some feeling and movement below the level of injury. More than

half of the key muscles can move, but not strongly enough to generate movement against gravity. Moving against gravity means, for example, raising your hand to your mouth when you are sitting up.D: Incomplete. There is both some feeling and movement below the level of injury. More than half of the key muscles can move against gravity.

E: Incomplete. Feeling and movement are normal, though there may be damage to vertebrae.In summary, an injury is described as complete if there is no voluntary motor (movement) or sensory function below the level of injury. If the arms are spared, the injured person has paraplegia. If they are involved, the person has tetraplegia. The level of injury is the lowest intact spinal cord segment.

Consequences of the level of injury

It is completely rational that in the early phases of treatment, surgical and medical care is tailored to the needs of the individual and based on the specific nature of their injury. Once rehabilitation starts in the hospital, the therapy provided will also be tailored to some extent to the level of injury and will aim to teach self-care and everything the injured person needs to maximise independence.

Patients can get frustrated when they perceive fellow patients to be receiving ‘more therapy’ than they are themselves. This is because their assumed potential for recovery to some extent dictates how scarce resource is provided in the hospital system. Once we recognise that regaining some control is a fundamental driver for any person in this situation, this frustration becomes understandable. I have never met anyone who’s complained they received too much therapy.

The danger comes when a shortage of resources is the real driver for what happens clinically rather than the injured person’s potential for benefit. In the past, many rehabilitation programmes have relied mainly on expert opinion, but evidence-based approaches are now becoming more apparent. In addition to the ASIA score, other measures that may be used in clinical practice include the Spinal Cord Independence Measure and Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury II (WISCI II) scale, and the Short-form Health Survey (SF-36) quality of life test. These useful measurements are intended to aid decision-making for treatment and rehabilitation, taking into consideration the individual’s capacity and expectation to reintegrate into society.

Limitations of an ASIA score

I have met lots of people who initially see their ASIA classification as an absolute marker of what is going to be possible for them. From the clinical-management point of view, it is essential to have measurement tools, but patients can see these as representing insurmountable barriers. Then they are surprised that a later therapy intervention reveals a function they believe they are ‘not supposed to have’.

Spinal cord injuries are highly variable. We can only compare two people, both with injuries to their spine and even with the same ASIA score, cautiously concerning their capabilities or functional recovery patterns. Spinal cord injuries are also highly heterogeneous, which means it is challenging to assess the value of treatments to individuals. An accurate ASIA score is useful – after all, that is its intention – but never consider it a ‘tablet of stone’.

An optimistic view of spinal cord injuries is that most are in a practical sense incomplete – even the ones that seem otherwise. This suggests that many patients can transmit information from the brain to affected muscles through spared, albeit fragmented, neural networks. In addition, when we consider that an injury that damages the spinal cord often spares the brain, the advantage of an incomplete injury becomes even more powerful.

An incomplete injury suggests a great opportunity for functional recovery. It does not make recovery easy, though, and experts are still striving to learn how to take advantage of this potential.

References

American Spinal Injury Association (1982) Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Injury Patients. American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA)

Frankel, HL et al (1969) ‘The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia’, Paraplegia, 7, pp179–192

This article is based on a section in the book "Dont Back Down - Your Guide to Living Well with a Spinal Cord Injury" by Anatomical Concepts Director, Derek Jones PhD, MBA. The book is available on Amazon in print and as a Kindle book.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Dont-Back-Down-living-spinal-ebook/dp/B0BNP1XGZ2