Complete vs. incomplete spinal cord injury: What you need to know

A spinal cord injury is a life-altering event that can happen to anyone, anywhere, and at any time. It can occur due to a wide variety of reasons, such as accidents, falls, sports injuries, or medical conditions.

The severity of a spinal cord injury varies greatly and each person, even with what can seem to be similar injuries, can have different symptoms and functional outcomes. As part of the clinical approach to understanding and managing such injuries, a system of classification has been developed.

When people are injured, they are often told that they have damage to specific bony vertebrae and the cord itself at a given level, along with a further qualifier suggesting the severity of the injury, typically as a ‘complete’ or ‘incomplete’ injury. But what do these terms mean, and what is their significance?

The system commonly used to classify a spinal cord injury now is the American Spinal Injury Association system or ASIA score. Understanding the differences between a complete and incomplete spinal cord injury is important for patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. However, these labels are not always understood by patients and we should be cautious about how we interpret these.

So, let's dive in and discover what you need to know about complete vs. incomplete spinal cord injury and its effects on the nervous system.

The nervous system

When your nervous system is working properly, it carries electrical and chemical “messages” to and from your brain and body parts. The nervous system is complex, but in essence, these messages control at least three important functions:

The motor functions determine your ability to coordinate and control the contraction of your muscles consciously and deliberately, and hence the movement of your limbs to carry out everyday tasks.

The sensory functions that reflect the sensation of touch: your ability to ‘feel’ things and be aware of the position of your limbs in space even with your eyes closed.

The autonomic functions, refer to actions that your brain controls without you having to think about them. Your heart beating and your lungs taking a breath are examples. Interestingly, just because functions are autonomic, it does not mean that you cannot consciously influence them. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) has a powerful effect on many organ systems and is central to how we all behave under stress.

In basic terms, the closer the damage to the spinal cord is to the head and neck, the more parts of the body are affected and potentially the greater the degree of disability. This is because the nerves at a particular vertebrae level represent a part of the communication path between the brain and the various body systems below that level.

When the spinal cord is damaged, messages cannot ‘jump over’ the damaged area. In other words, the messages sent from the brain cannot make it to body parts below the damaged area, and vice versa. Thus, the body at and below the level of injury is affected, but our bodies are resilient, and the nervous system will attempt to ‘rewire’ itself and work around the problem. Current research and clinical practice tend to encourage this process in a manner that might produce recovery of function.

The discovery of the nervous system’s ability to regenerate (neuroplasticity) is often discussed, poorly understood yet, but the source of much optimism is that certain activities can help the nervous system optimise recovery following a brain or spinal cord injury. Technology such as the Locomat shown below moves the legs in a repetitive fashion which sends information from the moving limbs back to the brain. Why and how this works is beyond the scope of this article but has been discussed in other articles on this site.

Using a Locomat exoskeleton to encourage neuroplasticity and functional recovery

Understanding spinal cord injuries

The spinal cord is a bundle of nerves that run from the brainstem down the whole of the back and protected by the bony spine.

A spinal cord injury occurs when the spinal cord itself is damaged. As we described above, the location and severity of the injury will determine the nature and extent of the damage, the parts of the nervous system affected and the resulting symptoms.

People who sustain a spinal cord injury require urgent specialised care. It’s not just a matter of survival; the nature of the immediate care has major implications for the individual’s avoidance of complications and prospects for the long term. Complications damage an individual's prospects for recovery and can have profound effects.

The timeline of a spinal cord injury caused by trauma is often described as consisting of a primary and a secondary phase.

The primary phase might (for example in a car accident) – be mechanical and mainly due to the trauma to the spinal column, which in turn exerts a force on the spinal cord it surrounds, resulting in disruption of axons (nerve fibre). This is most commonly the result of a compressive/bruising injury that causes shearing, laceration or acute stretching of the cord. But here is an important point that we will revisit later in this article.

Injuries that fully cut through the spinal cord are rare and usually, some connections are spared. It is true that with both incomplete or complete injuries, the spinal cord may not be completely severed.

This seems to suggest that some functional recovery should be possible and research is ongoing for potential therapies that would optimise such recovery, which means at least preserving and developing the remaining connections.

However, these remaining connections are at risk during the secondary phase of injury.

This secondary phase feature processes that the body initiates naturally as part of its inflammatory and healing response. But these “natural” processes – namely ischemia, excitotoxicity, cardiovascular dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation that leads to cell death – are damaging to the potential for recovery. At work, they are often harmful to the surviving neurons, and damage to these neurons can lead to poor motor function recovery.

During this secondary phase, an internal environment is created that seems to impair the potential for regeneration. The secondary phase is made up of several sub-phases that are divided over time into the so-called immediate (first two hours), acute (two to forty-eight hours), subacute (forty-eight hours to fourteen days), intermediate (fourteen days to six months) and chronic (six months and beyond) stages of injury. Typically, early therapy is designed to target the events that occur in a particular phase.

Spinal cord injury levels

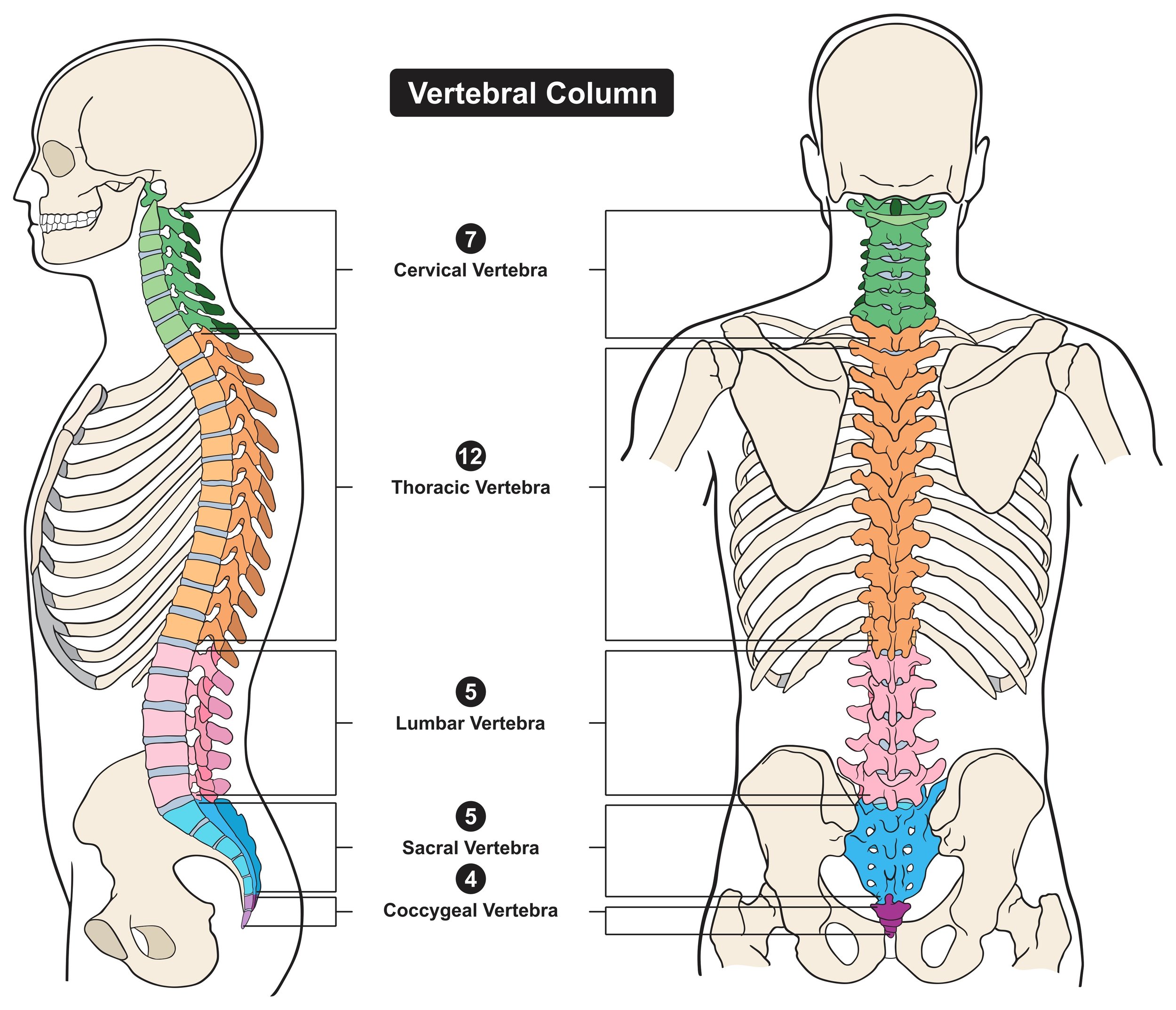

The definition of spinal cord injury levels and the classification of the injury with the ASIA score can seem confusing if you haven’t met them before. A basic description of the vertebral column is depicted below along with the consequences of injury at various levels of the spine:

The vertebral column

Cervical. The neck area contains seven cervical vertebrae (C1 to C7) and eight cervical nerves (C1 to C8). Cervical injuries usually cause loss of function in the chest, arms and legs. They can also affect breathing and bowel and bladder control. These effects are in addition to loss of function in the thoracic, lumbar and sacral regions.

Thoracic. At the central chest area, there are twelve thoracic vertebrae (T1 to T12) and twelve thoracic nerves (T1 to T12). Thoracic spinal cord injuries usually affect the chest and the legs. Injuries to the upper thoracic area can affect breathing. Thoracic injuries can also affect bowel and bladder control.

Lumbar. The lumbar area (between the chest and the pelvis) contains five vertebrae (L1 to L5) and five nerves. Lumbar injuries usually affect the hips and legs, and can also affect bowel and bladder control.

Sacral. The sacral area (from the pelvis to the end of the spine) contains five sacral vertebrae (S1 to S5) and five sacral nerves (S1 to S5). Sacral spinal cord injuries usually affect the hips and legs. Injuries to the upper sacral area can also affect bowel and bladder control.

For example, in an injury between C1 and C8, messages to and from the brain are stopped in the neck area. This usually results in at least some paralysis of the chest, arms and legs (tetraplegia, also known as quadriplegia). In an L3 injury, messages are stopped at the lower back. This results in at least some paralysis of the legs and hips, which is commonly referred to as paraplegia.

The ASIA Score

Spinal cord injuries are typically classified using the internationally agreed approach we mentioned above in the introduction - the ASIA score. As we learned earlier, injuries are often described as consisting of the vertebrae level and then as complete or incomplete. The ASIA system further classifies incomplete injuries into four subsections:

A: Complete. No feeling or movement of the areas of your body that are controlled by your lowest sacral nerves. This means you do not have feeling around the anus or control of the muscle that closes the anus, so people with ASIA A, complete spinal cord injuries do not have control of bowel and bladder function.

B: Incomplete. There is feeling, but no movement below the level of injury, including sacral segments that control bowel and bladder function.

C: Incomplete. There is both some feeling and movement below the level of injury. More than half of the key muscles can move but are not strong enough to generate movement against gravity. Moving against gravity means, for example, raising your hand to your mouth when you are sitting up.

D: Incomplete. There is both some feeling and movement below the level of injury. More than half of the key muscles can move against gravity.

E: Incomplete. Feeling and movement are normal, though there may be damage to vertebrae.

Diagnosis and treatment of spinal cord injuries

We won't cover diagnosis and treatment in depth in this article, but basically, the diagnosis of spinal cord injury involves an assessment of the person's sensory and motor function, reflexes, and muscle tone. Diagnostic imaging tests, such as X-Rays, CT scans, or MRI, will be used to identify the location and severity of the injury. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the doctor will determine the type and level of spinal cord injury to develop an appropriate treatment plan. The image below shows a X-Ray image on the left and an MRI of the cervical spine in a trauma case. The red arrow is pointing to a joint dislocation and facet fracture. Note the spinal cord is compressed but intact.

There is currently no cure for a spinal cord injury, and the focus of treatment is on first managing symptoms and preventing complications. Once the person is medically stable, the primary goal is to help the person maintain their physical health, prevent secondary complications, and maximise their quality of life through a process of rehabilitation.

Treatment for spinal cord injury may involve a combination of medication, surgery, and rehabilitation. The person may need medication to manage pain, muscle spasms, and other symptoms. Surgery may be required to stabilise the spine and prevent further damage.

Consequences of the level of injury for rehabilitation potential

Rehabilitation is a vital component of treatment for all spinal cord injuries whatever the injury classification although of course, the goals will differ.

The person may need physical therapy, occupational therapy, and other forms of therapy to help them regain as much function as possible. But just what function can be recovered? This is never easy to be certain about. They may also need assistive devices, such as wheelchairs, braces, and other mobility aids.

Theoretically, the ideal process is one that aims for restitution of all function that is possible to recover and then compensate for what cannot be recovered

Of course, the theory is one thing and practice is another!

In our experience, no one recovering from a spinal cord injury ever complained they received too much therapy. The NHS is not resourced adequately to provide more than the minimal amount of rehabilitation intervention and many persons will seek private provision or charity support.

It is completely rational that in the earliest phases of treatment, surgical and medical care is tailored to the needs of the individual and based on the specific nature of their injury. The focus is on survival and achieving medical stability.

Once rehabilitation starts in the hospital, the therapy provided will also be tailored to some extent to the level of injury and will aim to teach self-care and everything the injured person needs to maximise independence.

Patients can get frustrated though when they perceive fellow patients to be receiving ‘more therapy’ than they are themselves. This is perhaps because their assumed potential for recovery to some extent dictates how scarce resource is provided in the hospital system. Once we recognise that regaining some control is a fundamental driver for any person in this situation, this frustration becomes understandable.

The danger comes when a shortage of resources is the real driver for what happens clinically rather than the injured person’s potential for benefit.

In the past, many rehabilitation programmes have relied mainly on expert opinion, but evidence-based approaches are now becoming more apparent. In addition to the ASIA score, other measures that may be used in clinical practice include the Spinal Cord Independence Measure and Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury II (WISCI II) scale, and the Short-form Health Survey (SF-36) quality of life test. These useful measurements are intended to aid decision-making for treatment and rehabilitation, taking into consideration the individual’s capacity and expectation to reintegrate into society.

Limitations of an ASIA score

I have met lots of people who have initially seen their ASIA classification as an absolute marker of what is going to be possible for them. From the clinical-management point of view, it is essential to have measurement tools such as the ASIA score, but patients can come to see these as representing insurmountable barriers. They create an expectation of possibility (or of limitation). Clinicians may wish to prevent their patients from having unrealistic expectations about their possibilities for recovery and definitely, some may need to be nudged in the direction of acceptance. Some personality types will resist this and always wish to find ways to strive for recovery.

I have certainly met many persons who were told that because of their ASIA score, they would never be able to do “this or that”. These individuals are then surprised that a later therapy intervention reveals a function they believe they are ‘not supposed to have’.

As spinal cord injuries are highly variable, we can only compare two people cautiously even with the same ASIA score and it is hard to predict their capabilities or functional recovery patterns. Spinal cord injuries are also highly heterogeneous, which means it is challenging to assess the value of treatments to individuals.

An accurate ASIA score is useful – after all, that is its intention – but never consider it a ‘tablet of stone’.

An optimistic view of spinal cord injuries is that most are in a practical sense incomplete – even the ones that seem otherwise. This suggests that many patients can transmit information from the brain to affected muscles through spared, albeit fragmented, neural networks. In addition, when we consider that an injury that damages the spinal cord often spares the brain, the advantage of an incomplete injury becomes even more powerful.

An incomplete injury suggests a great opportunity for functional recovery. It does not make recovery easy, though, and experts are still striving to learn how to take advantage of this potential.

Conclusion

Any spinal cord injury is a life-altering event that can happen to anyone, anywhere, and at any time. The severity of spinal cord injury is normally described in terms of an ASIA score, and each level and score has distinct symptoms and outcomes. Understanding the differences between complete and incomplete spinal cord injury is important. It is important for anyone who has experienced such an injury to know as much about their condition as they can.

However, it is important not to treat such classifications as "tablets of stone". Whether your injury is complete or incomplete there will always be things you can do to improve your fitness and long-term quality of life.

Initial treatment for spinal cord injury focuses on managing symptoms, preventing complications, and maximizing quality of life. This is something you can have little control of. Rehabilitation though is different. Rehabilitation is an essential component of treatment and helps the person regain as much function as possible. Rehabilitation is not something that is done to you - you have to see it as something you will need to engage in and embrace.

Rehabilitation will typically involve exercise-based therapy which should be seen as something that ideally is carried out for the rest of the person’s life. This is no different than for any human. One of the essential ingredients of a long life is exercise which focuses on developing and maintaining functional strength and cardiovascular fitness. This is true for everyone - spinal cord injury or not.

Recovery from spinal cord injury can be a long and challenging process, but with the right treatment and support, the person can lead a fulfilling life.